Now it’s 2024 and, suddenly in the mood to replay some old arcade games, I decided it would be a fun project to revisit my old Picade and see about giving it an upgrade.

The last decade

My Picade, and the “consolized” version I made later, haven’t been the center of my retro gaming for some time now. These days, besides original hardware, I usually play retro games on any of a variety of emulation handhelds, or on my custom Genesis Mini with my son. The little arcade machine has spent the last few years in a cabinet in the game room, but it wasn’t always tucked away. I used to keep it at the office when I worked for Xbox, and it got plenty of play during breaks. And while the original Pi powering it struggled with anything but the oldest arcade games (I distinctly remember a long running Flicky competition) I was still proud of it. But ever since I started working from home, the Picade sat collecting dust while I got my retro fix elsewhere.

It still works, mostly

Dusting it off and flipping the switch, I was glad to see it boot up exactly as I’d left it. My intent had always been for it to be more appliance than computer, so it didn’t matter that it hadn’t gotten a software update in a decade. It was like a little time-capsule of the early days of RetroPie-based projects, and it still worked.

Well, software-wise, it worked as well as it had ten years ago. But there were more than a few hardware issues (some new, some forgotten) that I decided would need addressing.

First off were the controls. The joystick was fine, but the buttons were just downright flaky. Some required you to mash them to register – some would register just by gently wiggling them without even pressing down. Not only that, none seemed to have a solid grip on the cabinet and could be easily popped out with just your fingers. So I was definitely in the market for new buttons.

The controller board still worked – it’s basically an Arduino Leonardo set up to emulate a USB keyboard – and I’d already customized the keys years ago, but that had also meant manually configuring each emulated system. Thankfully I knew both Arduino libraries and the Emulation Station controller setup had come a long way since then, and so I figured I could probably just rewrite the board to emulate a USB gamepad instead and be done with it.

One persistent issue had been the audio. The original controller board was also set to pipe audio to the speakers, but the signal was noisy and required you to use software-based volume controls, which I always hated. One of the final mods I’d done before was to install a dedicated audio amp and external volume knob. It’s not perfect – it is still unnecessarily noisy, especially at lower volumes or at quiet points like in-between levels. If you click off the volume knob it’s silent, but then there’s an annoyingly loud “pop” when you first turn it on. I figured it wasn’t worth messing with. Foreshadow… foreshadow…

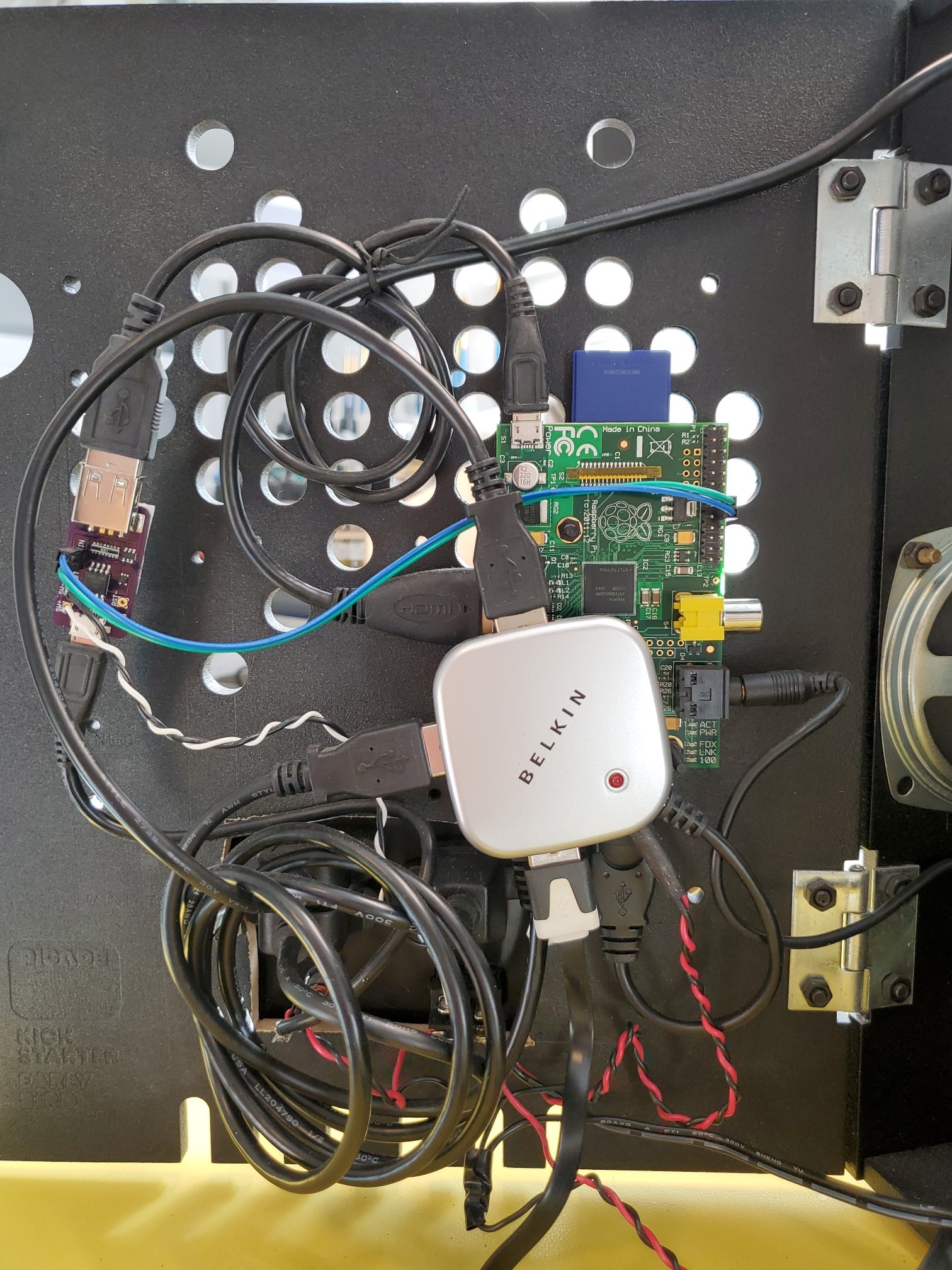

The last issue was power – the old Pi needed a solid amp, and it didn’t really want you pulling too much more to power USB devices through its two built-in ports. So I used a 3A supply to power four devices in parallel: the Pi (through a Mausberry board for safe shutdowns), the monitor, the audio amp, and a homemade powered USB hub. I say homemade as I basically took a regular hub, cut the power lines to the input plug, and ran my own lines direct to my power jack.

The end result was four ports: one for the controller board, two for the plate on the back of the cabinet, and one still free, none pulling their power through the Pi. While I never plugged in anything more than a keyboard, I didn’t want to risk frying the Pi. This time around, I figure I can probably simplify things and just use the four built-in ports most newer Pis have.

Planning a new aesthetic

When I first built the Picade, the goal was to add every system I cared about with their full library, as an all-in-one retro gaming solution. I added every game ROM I could find, which in the end really made navigating and finding a game a bit of a chore. The “launcher” program, Emulation Station, was an ancient build by today’s standards, and just displayed giant plain text lists of ROMs for each configured system. To top it off, I only ever played a few games on it, usually the few working arcade games or their console ports.

I often fill up emulation devices with a system’s entire library, usually grouped into alphabetical folders using RomSort. It can be nice to know that I could drop into any game at any time. But I really enjoyed the experience of building the Genesis Mini, and rather than copying every single Sega game, taking the time to curate a small list of just my favorites. I decided early on, that if I was really going to upgrade the Picade, that I was going to stick to a curated list of arcade games I actually wanted to play. I wanted the system to feel like my Picade.

That decision to make the machine feel more personal to me, extended beyond the software setup. While the existing cabinet art was fine (and my favorite of the options in the original Kickstarter) I knew I wanted to really lean in and make it exciting for me to look at. Something that made me want to sit down and turn it on.

I decided I wanted to go with a Street Fighter design – some of my fondest “arcade” memories were of playing on an Street Fighter II Champion Edition cabinet at the San Pablo Reservoir where my grandfather used to work. The machine was outside the bait shop, sun-bleached and beat to hell, but I loved playing on it. I found high-res scans of that art at Arcade Artwork, so it was just a matter of reworking it for my mini machine.

Capturing some final media for posterity

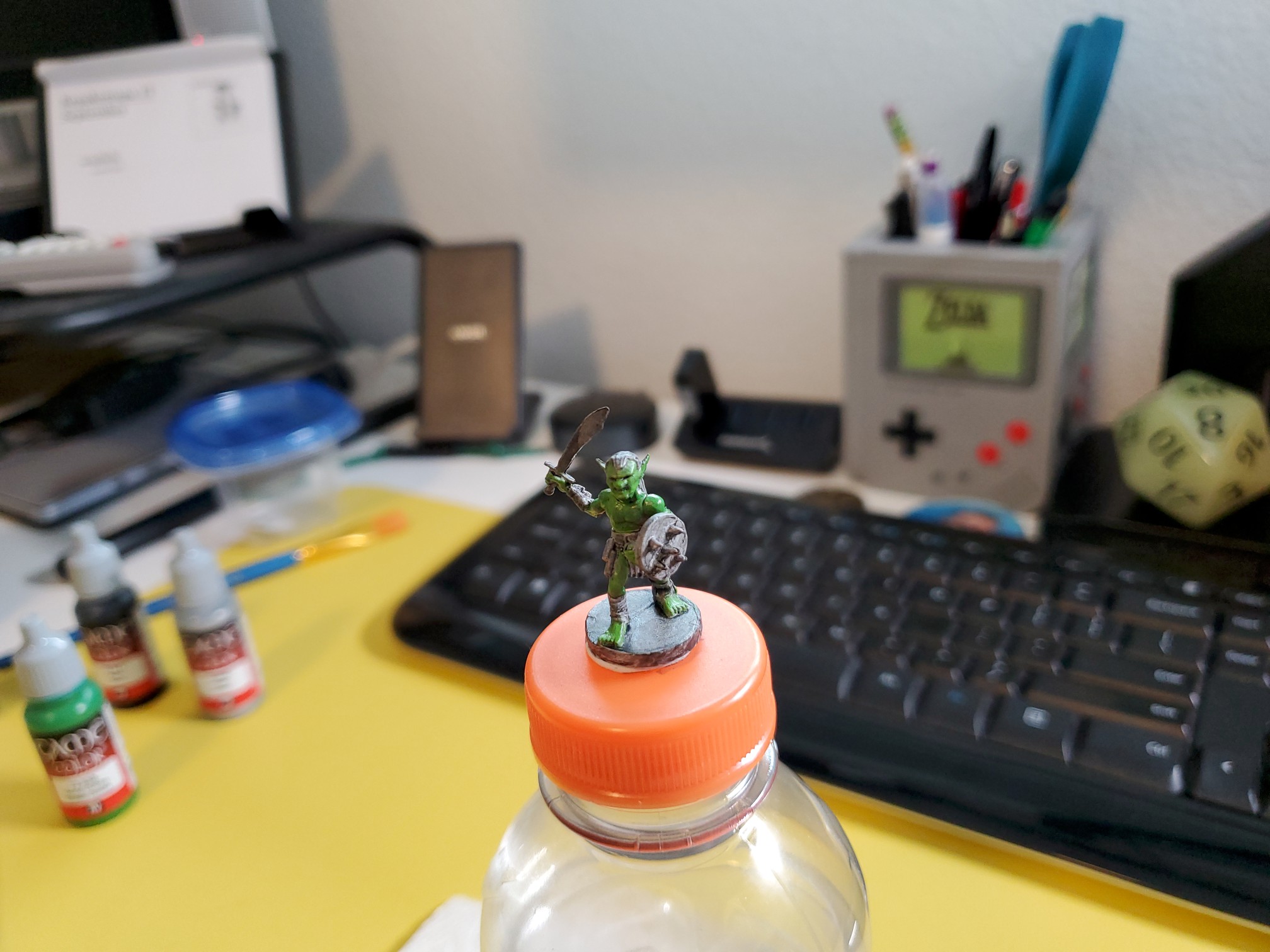

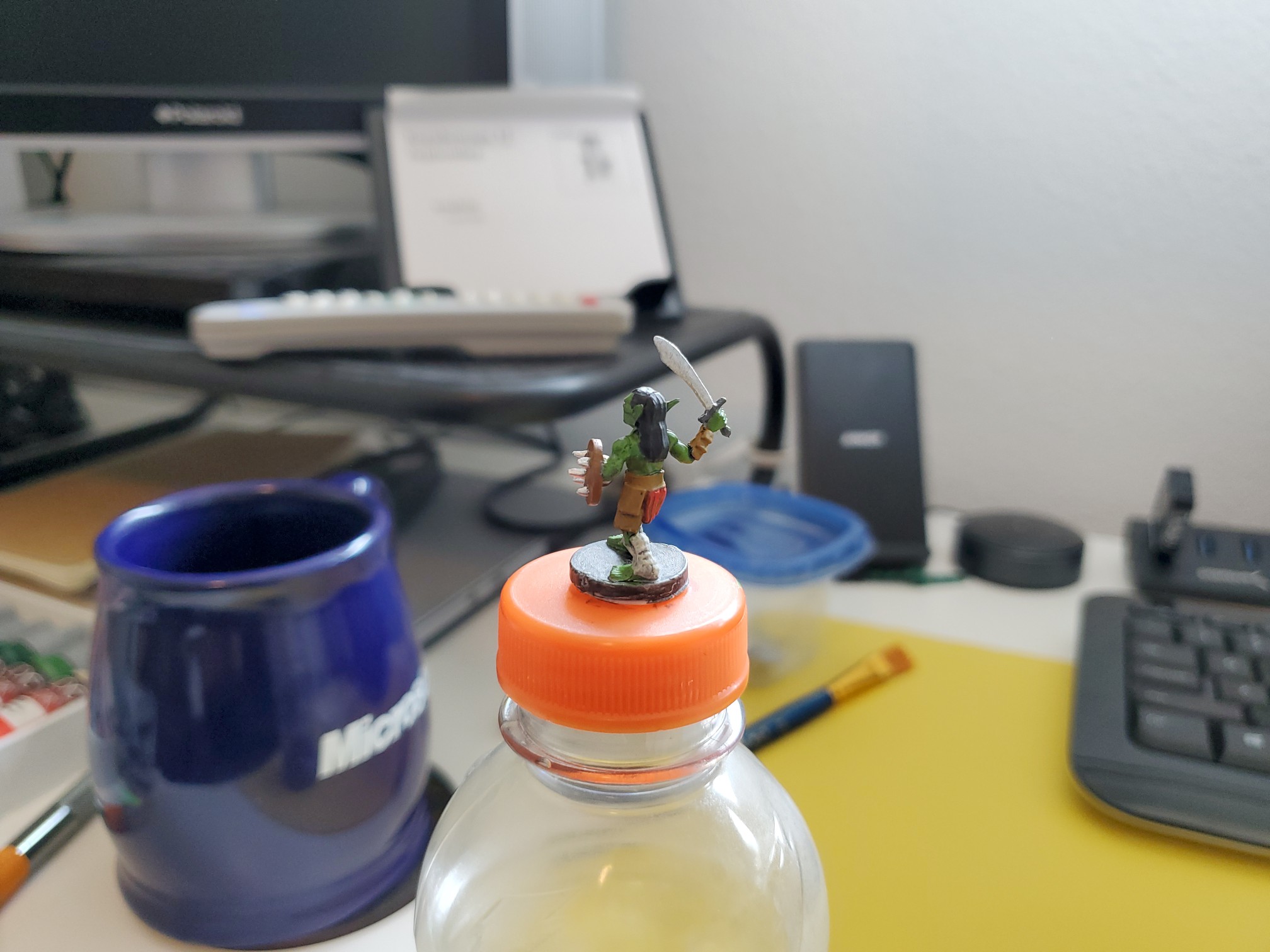

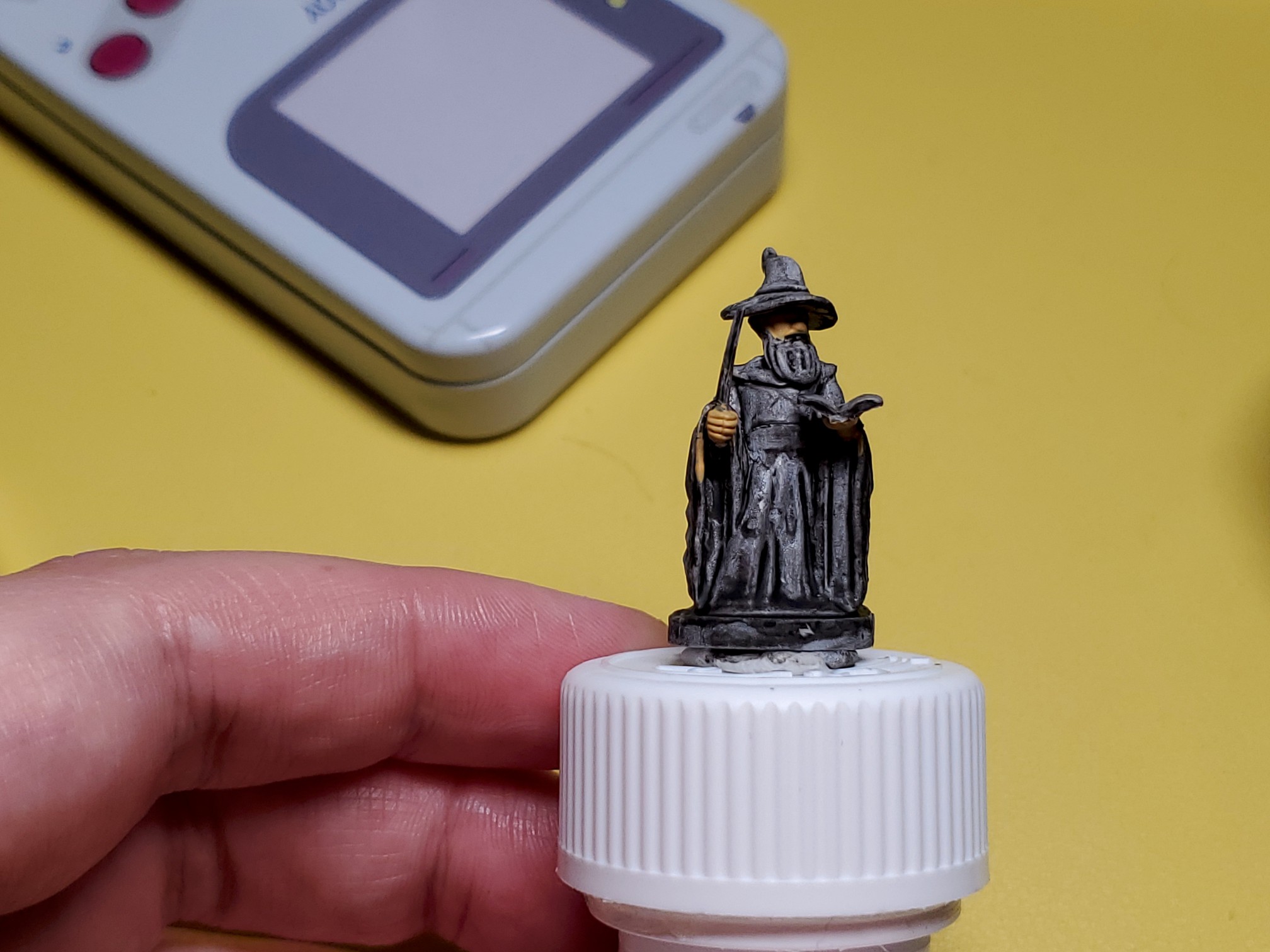

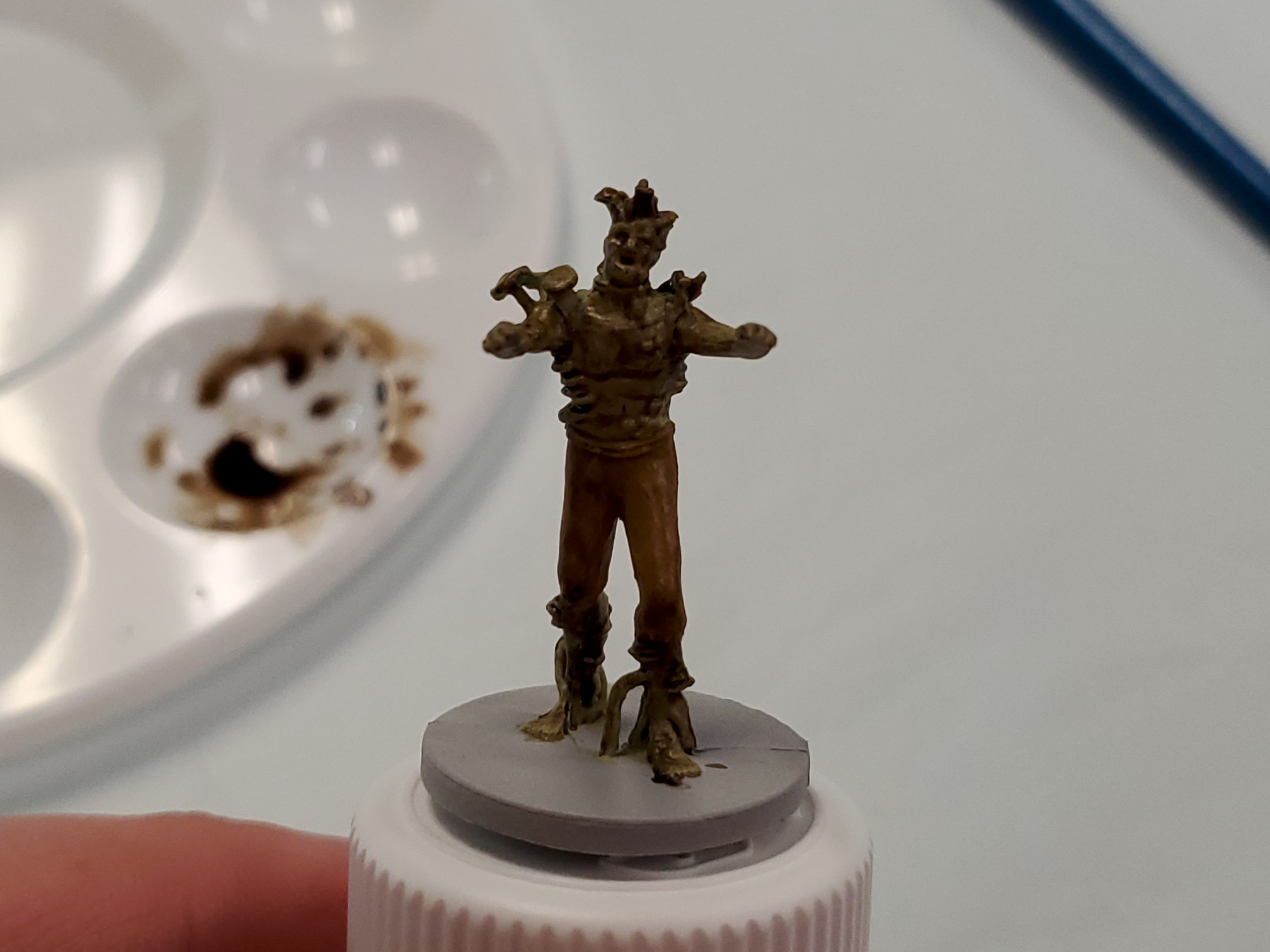

Before getting started with the upgrade, I decided I wanted to capture some final footage of the old Picade:

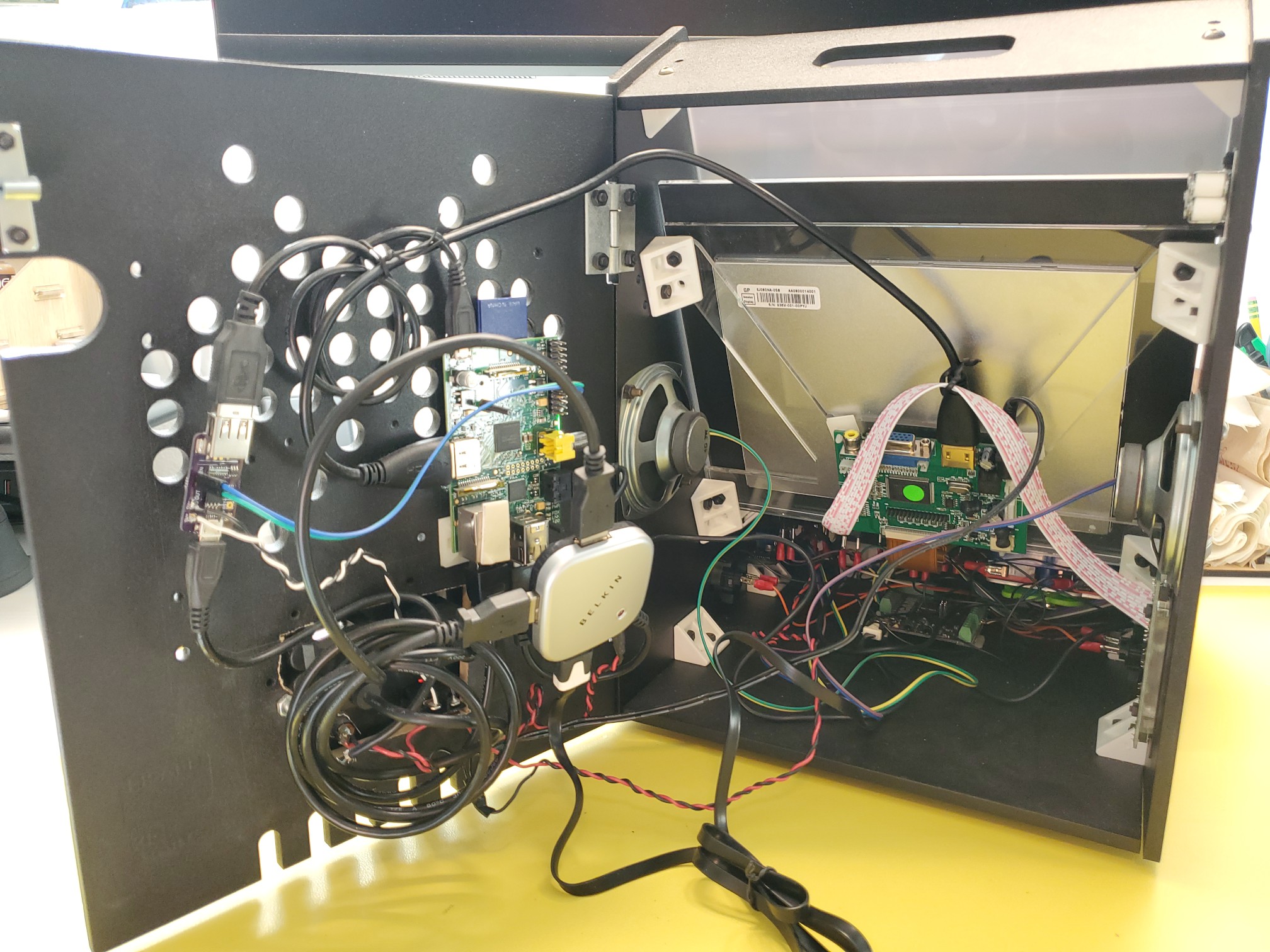

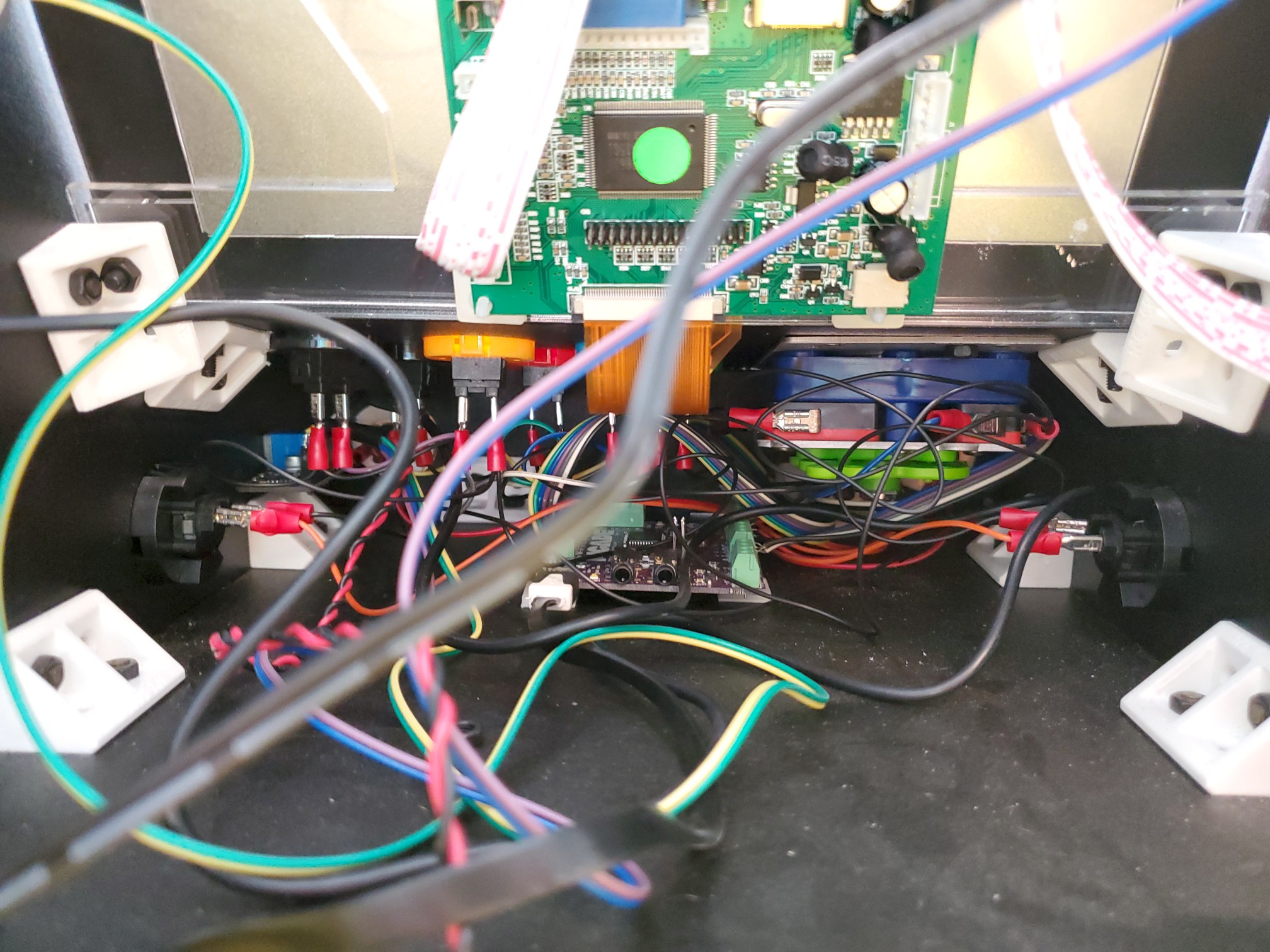

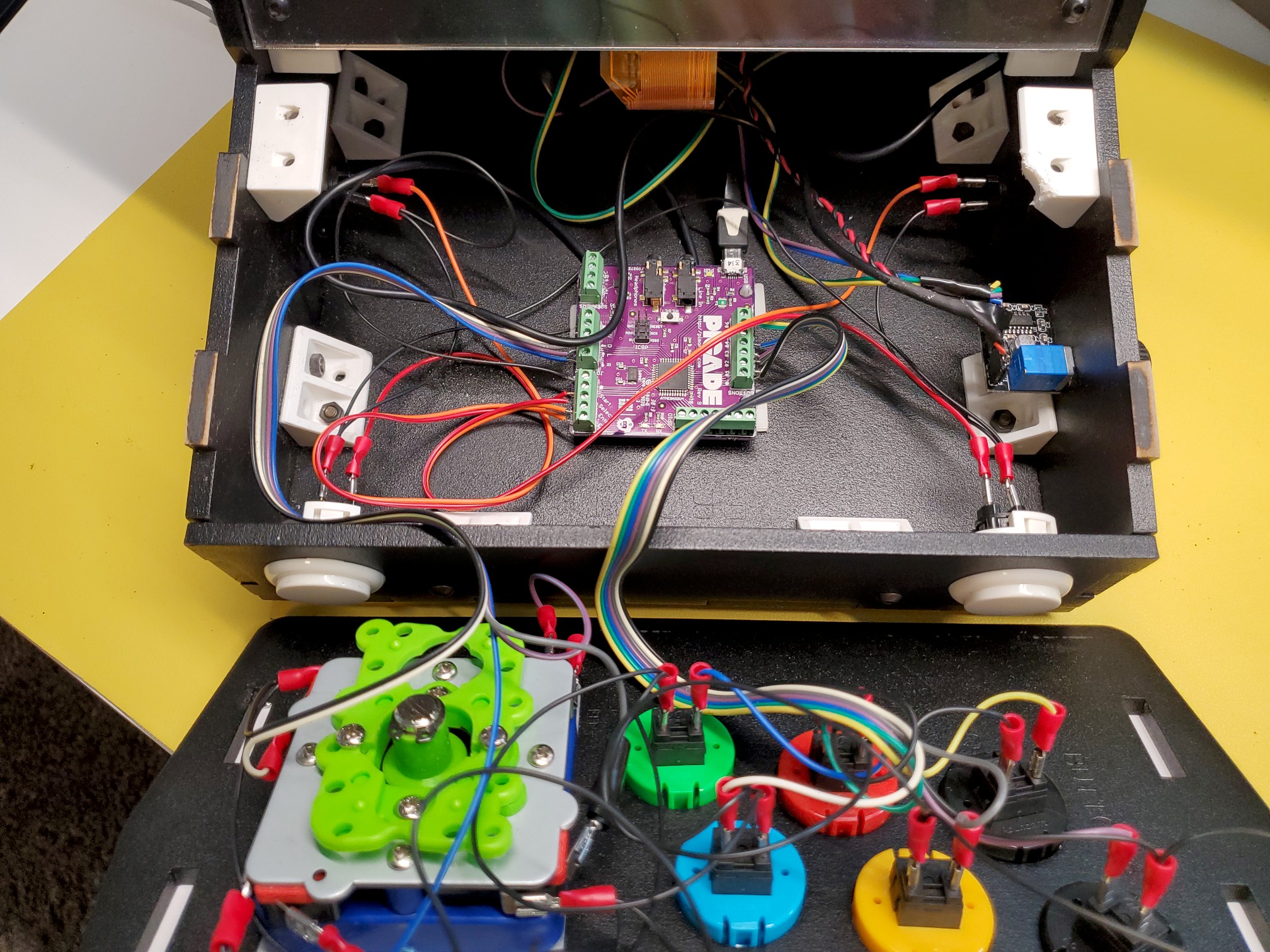

And just so I wouldn’t have to scrub through that video for clues (in case I messed something up), I also took some final photos of the inside:

Buying some new parts

Once I had that final video and the aesthetic plan in place, I started tinkering and shopping for new parts.

I picked up a Raspberry Pi 3B for the new computer, knowing it’s not the newest or most powerful board, but trying to balance budget with my stated goal of just running a small selection of arcade games. It had everything I needed for a quick swap: 4 USB ports, micro-USB input, full HDMI output, and 3.5mm output for audio. The Picade only has a 640×480 monitor anyway – it’s not like I need one of the newer 4K-capable Pis.

The only other parts I needed were new buttons. I decided that, in keeping with the Street Fighter design, to switch away from the Japanese Sanwa-style buttons to Happ-style buttons, the kind favored by US arcades, as well as a “bat” top for the joystick. Unfortunately, real (or knock-off) Happ buttons are very long, and definitely wouldn’t fit in the Picade. Thankfully, I found the Canadian-based Retro Active Arcade, which carry Concave Fusion buttons – buttons with Happ-style tops but shorter by using Sanwa-style internals. Best part, they use locking rings to lock them place (no more easily removable buttons).

Designing some new cabinet art

While waiting for my new parts to arrive, I got to work designing the new cabinet art. Thankfully the original Picade Kickstarter included to-scale PDF blueprints for all of the parts. So with a little work in Inkscape, I was able to create SVG templates that I could then fit the art to. I started with the simplest piece, creating a new marquee (my marquee SVG template):

That was a pretty straight forward resize of the original art, so next I went to work on the control panel (my control panel SVG template). I started with a clean base of the black and grey pattern, then added the joystick circle in the right place. The button design took a little more work, as the original machine had six buttons arranged in a rectangle, while the Picade had a more modern, slanted parallelogram layout.

But once I was happy with my design, I printed our some mocks to check the size:

New buttons, new control panel, new marquee

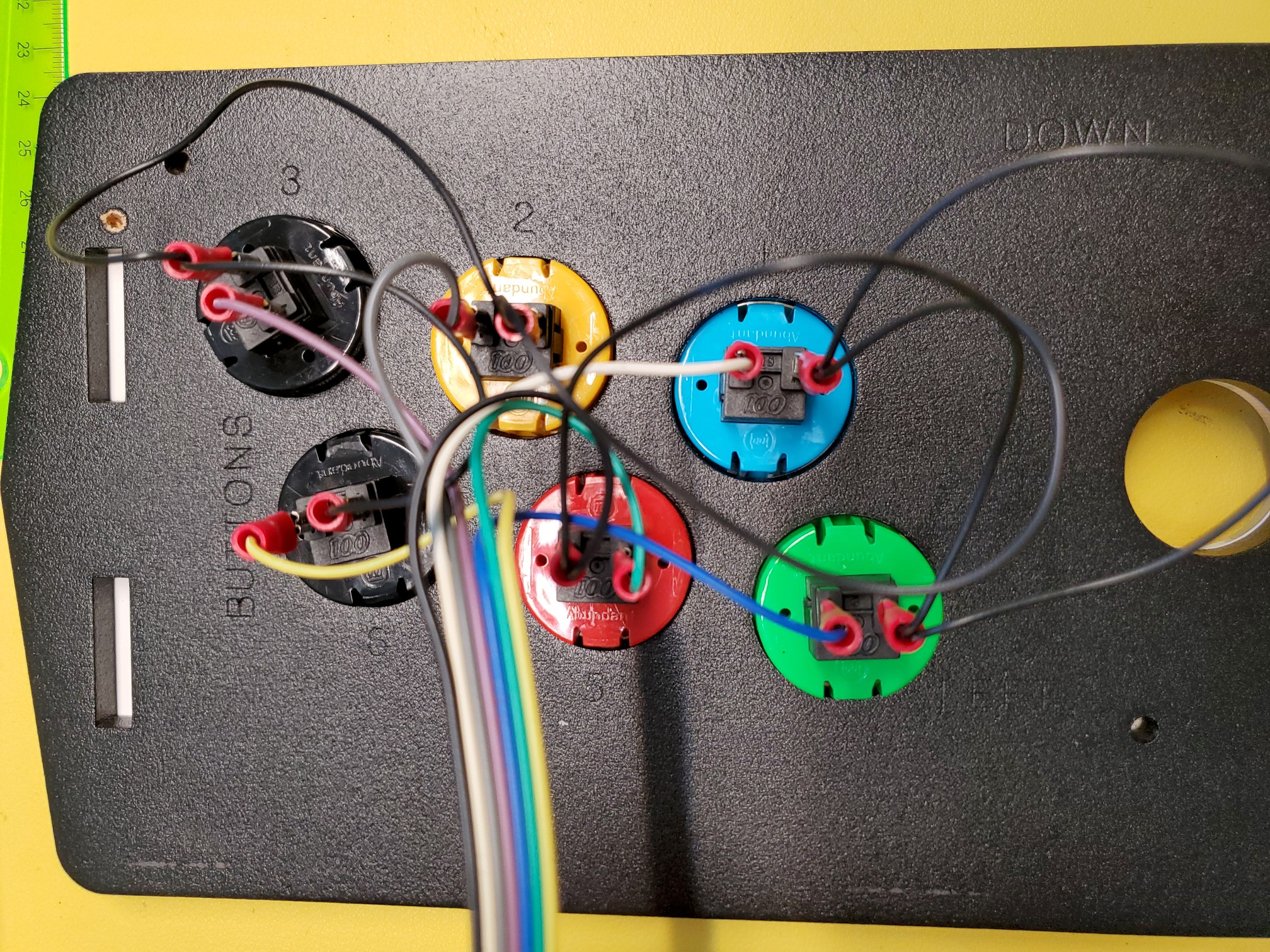

With the mock-ups done (they fit perfectly), I began disassembly, starting with the control board:

I replaced the buttons in the bottom of the cabinet first:

They fit perfectly, and with the locking rings they weren’t going anywhere. But one thing I noticed (and this will come up later) was that the wires for the audio amp (on the far right) looked pretty smashed and sketchy looking. Anyway, I continued on with the control panel, replacing the buttons and the art all at once:

Finally I printed and installed the marquee:

Customizing the screen matte

It was when I’d gotten this far that I needed to make a decision about customizing the screen matte. The original black was plain and functional, but if I really wanted to capture the aesthetic of a Street Fighter II Champion Edition cabinet, I knew I’d want the official art with all of the character portraits. So I went back to the computer and started reworking the art to fit (my screen matte SVG template):

The hard part, I knew, would be installation. I’d have to remove the entire monitor assembly and break the seal on the existing screen acrylic, risking dust and debris getting inside. And I was right, it was a complete pain to do, as I not only had to re-remove the control panel and marquee, but all the monitor support mounts (and even the LCD panel itself) fell out as soon as I started to take it apart. I really had to rely on my “before” photos to get it all back together:

But with that finished, I think the final result was worth it:

A quick first test

Once I got everything back together, I decided it was time to quickly verify I hadn’t broken anything by starting it up with the original board (hence the incorrect screen resolution for the arcade game):

Upgrading the controller board

With new buttons installed and working, the next bit of work was to update the software running on the controller board (as mentioned above, basically just an Arduino Leonardo). Ten years ago, the best option was for the board to emulate a USB keyboard. Now, I’d already had experience changing that code, as I’d done so to pick my own key mapping back in 2014. But for this upgrade, I really wanted to ditch those limitations and emulate a proper USB gamepad instead.

Thankfully, someone’s already done the hard work, creating a Joystick Library for Arduino. So, using that, I quickly modified the existing controller code to send joystick inputs instead of keyboard inputs (my joystick code). It was quick and easy and worked perfectly!

Installing the Raspberry Pi 3B

With the controls and art complete, I figured it was okay to replace the original Raspberry Pi with the shiny new Raspberry Pi 3B and a fresh SD card flashed with Batocera, a very polished linux distro for optimized for playing retro games.

And that’s when a whole new host of problems reared their ugly heads.

First off, the board simply wouldn’t boot, giving an “undervoltage” error. Turns out I hadn’t accounted for the extra power the new Pi would draw – my 3A supply simply wasn’t enough to run the Pi, the screen, and the controller. So I ordered a 6A power supply and twiddled my thumbs until it arrived. With that in place, I got the machine to boot, and even load a game:

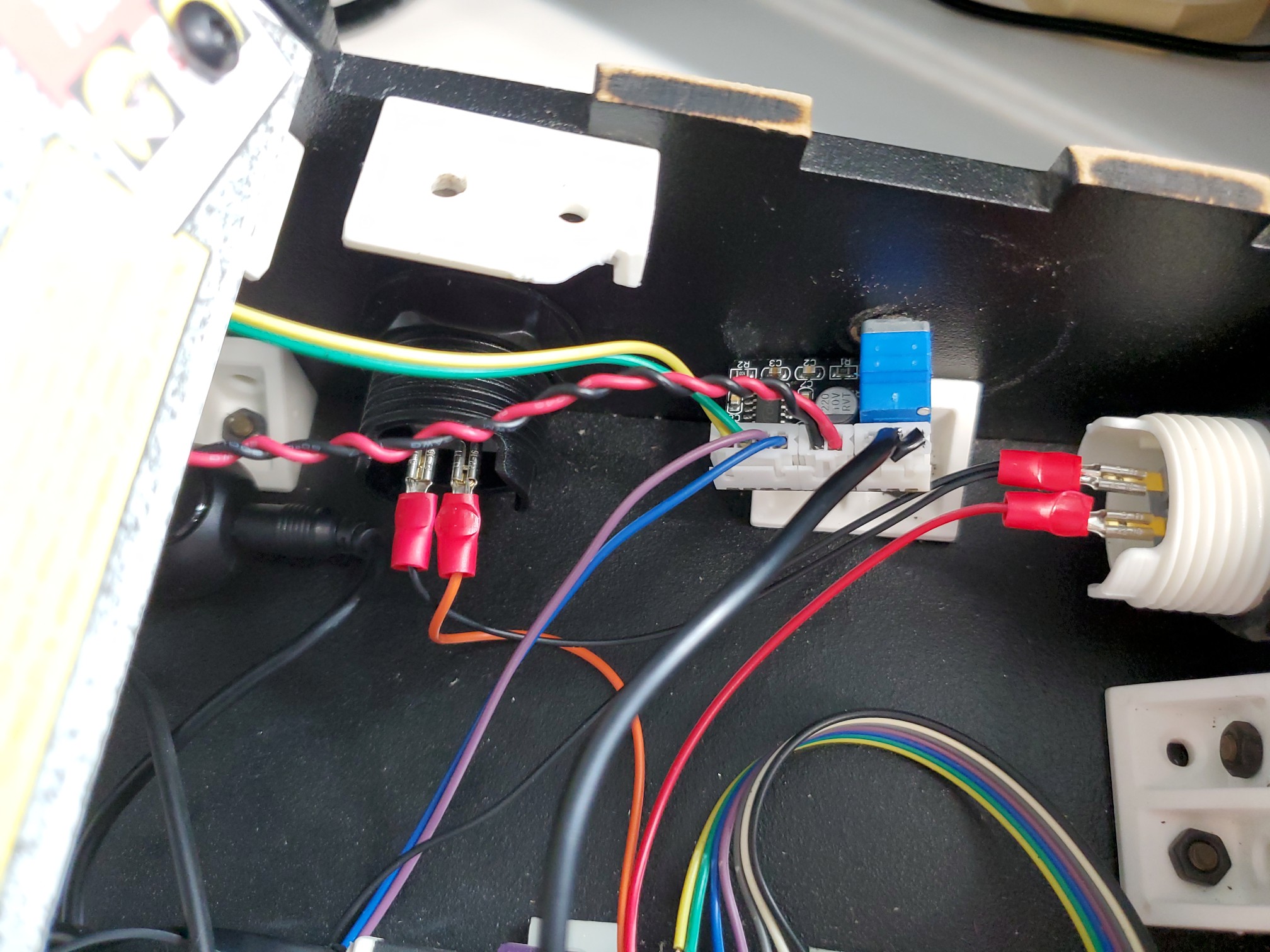

Everything was (mostly) fine, unless I touched anything inside while it was running. The machine would lock up or reboot, or there would be a healthy increase in noise coming from the speakers. I started by cleaning up some of my “early amateur soldering” for the monitor and amp power wires:

Then I decided to simplify the situation by removing my amateur “powered” USB hub as I’d already planned:

Fixing the audio problems

Even with that wiring cleaned up, there was still a problem with the audio. The noise coming from the speakers was atrocious, and worse, clicking on the amp caused some kind of power spike, causing the Pi to lose power for just a second and hard reboot.

I remembered how smashed the wires into the amp looked, and made the decision to open the control panel back up and rewire it. I removed the very ugly and amateur collection of electrical tape wrapped pins I’d soldered in place before, and installed actual JST connectors:

Unfortunately, even with those fixes, I couldn’t solve the issue with clicking on the amp causing the power spike. I’m not enough of a hardware guy to know what kind of circuit I need to protect against whatever transient condition happens when this (click on?) potentiometer makes first contact.

Regardless, I was able to finally get rid of the speaker noise. I rerouted all the wires so audio wouldn’t run parallel to power, made the power lines as short as possible, and installed a ground loop noise isolator. I also installed a proper 4 to 3 ring 3.5mm adapter, since the Pi 3B outputs both video and audio from its 3.5mm jack, and I didn’t want any noise from that.

So it wasn’t a perfect fix – if I turn on the main power with the amp clicked off, clicking it on will cause a hard reboot (and potential SD card corruption). If the amp is clicked on (even at the lowest volume), then I can turn it up and down without a problem, giving clean, noise-free sound. I can even click the amp off and back on when everything’s already running without a problem. So I’m just extra careful to never click it completely off, and that’s good enough for now.

The final bits

With the major issues addressed, the final bit of hardware was to install a couple heatsinks on the Pi. Not strictly necessary perhaps, but $4 for a little peace of mind was worth it:

With that final bit installed, I went ahead and copied over my favorite version of Street Fighter: Street Fighter II’ Hyper Fighting, and started it up for one final hardware test:

It worked perfectly, running at full speed and filling the screen, even with a video filter enabled to simulate the slightly fuzzy look of an older CRT screen. I love it.

Setting up Batocera

I won’t go through all the minutiae of setting up Batocera to my liking, but the experience was very satisfying. I changed the default boot and loading images to Street Fighter art, and set it to boot directly to my list of favorites. There’s a built-in menu to set up the Mausberry shutdown circuit, which was very nice and completely unexpected. I had to tweak some audio settings to deal with known audio issues with Raspberry Pis (which I didn’t know before), and I set up the WiFi so I could easily copy games over from my PC without having to shut it down and remove the SD card.

As for games, it’s mostly fighters and beat-em ups, but there’s some other classics on there as well. I’ve got about 100 arcade games on it already, and I’m running out of ideas for more. There’s even built-in “metadata scraping”, so instead of raw ROM lists, each entry shows the game title, the year it came out, a description and a screenshot. It’s all very slick.

The final result

I am thoroughly pleased with how the new Picade turned out. A little more work than I expected, but it only took me a couple days, not including waiting for items to arrive. To cap the project off, I filmed a video of the new Picade in action:

/jon